PBSCV1599

Gen. James Patton Anderson Camp 1599

Celebrating 34 Years 1992 - 2026

PART I

Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor

and his bride,

Margaret Ann Drane

The Doctor and the Spy"

A Southern Family

Compiled by Adj. Peter D. Johnston

Tichenor meets Drane

A historical and genealogical compilation on the life and times of the family - Descendants and Ancestors of Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor - CSA surgeon

and his wife - Margaret "Maggie" Drane

CLICK o n button to see the PDF version

(May take a minute to load - 245 pages)

Inventor of Dr. Tichenor's antiseptic products.

Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor was born in Ohio County, Kentucky, the son of Rolla and Elizabeth (Humphrey) Tichenor. He married Margaret Ann "Maggie" Drane, daughter of Rev. Thomas Jefferson and Margaret Ann (Thurman) Drane, November 12, 1863 at the Baptist Church in Liberty, Mississippi. She was born August 4, 1846 in Breckinridge County, Kentucky and died while on a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas to visit her brother, Robert, on November 8, 1924.

Dr. Tichenor was nicknamed "The man who made the Mississippi River," due to his study of this and other singular rivers and is accredited with changing the engineering policy of the government, opening the Southwest passes, and the building of the spillways, as opposed to the all-levee fallacy.

Initially, Tichenor was a businessman in Franklin (Williamson County), Tennessee when the American Civil War began. In 1861, he entered military service with the 22nd Tennessee Cavalry Regiment.

In 1863, he became an enrolling Confederate officer, and thereafter an assistant surgeon, during which time he is believed to have been the first in the Confederacy to have used antiseptic surgery. Tichenor experimented with the use of alcohol as an antiseptic on wounds. He was badly wounded in the leg in 1863, and amputation was recommended. He insisted on treating his wounds with an alcohol-based solution of his own devising. His wound healed, and he regained the use of his leg.

His potential reputation as a humanitarian was clouded by his fierce regional loyalty; Tichenor insisted that his techniques be used only on injured Confederates, never on Union prisoners.

An unconfirmed story was later circulated that Dr. Tichenor's antiseptic was granted the first patent issued by the Confederate government. An image of the Confederate Battle Flag remained on the product label well into the 20th century.

Tichenor developed his antiseptic formula in Canton and thereafter practiced medicine in Baton Rouge, LA from 1869-1887. He started bottling Dr. Tichenor's Patent Medicine in New Orleans; the formula, consisting of alcohol, oil of peppermint, and arnica, was originally marketed as useful for a wide variety of complaints for both internal and external use for man and animal. A patent was registered in 1882. The company producing this liquid was incorporated in 1905 and is still in existence, though the recommended uses are now more modest: principally as a mouthwash and topical antiseptic.

Dr. Tichenor had a younger brother, Thomas J. Tichenor (Memorial # 35975606) who was handicapped and never married. Thomas lived with Dr. Tichenor and his wife most of his adulthood and passed away at the Red River Landing home of his brother during the yellow fever outbreak. Yellow fever also took the lives of three of Dr. Tichenor's children: Waller LaRue, Sallie, and Mable. The children and Thomas are all buried there at Innis, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana.

Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor BIO from a speech given by Dr Osner at the Bicentennial Celebration in Liberty, Amite County Mississippi

These few are but a handful of famous Southern surgeons. There is one man, however that most of you are not familiar with, yet his name has been or is known by more people than any afore mentioned. Most of those previously mentioned will be forgotten with time, except by historians, or those similar interests, or intense players of Trivial Pursuit. In contrast, the name of the man I wish to speak of will continue to be known, not because of his achievements but because a patent medicine carries his name.

Dr. Tichenor was a multi-faceted Southern gentle man who was born in Ohio County, Kentucky, on April 17, 1837. He was the son of Rolla and Elizabeth Tichenor, both natives of Kentucky. His father was a merchant and steamboat owner and continued these pursuits throughout his life. George Humphrey Tichenor received the usual public school education of that time(which was somewhat limited in most sections of the South) in Rumsey, Kentucky. At age 13, upon his mother’s death and his father’s remarriage within the year, he ran away from home, taking his brother Thomas Jay, aged 11, with him, as they both felt unwanted by their stepmother who had five children by a previous marriage. His father’s second marriage ended a year later and he died two years later.

After leaving school, George devoted considerable time to the private study of chemistry. By 1859, he had moved to Nashville, Tennessee, and shortly after the beginning of the Civil War, he was commissioned by the Confederate government to manufacture gunpowder.

I would like to relate some of Dr. Tichenor’s experience as a Confederate soldier. At 24 years of age, in the spring of 1861, he enlisted in the Washington County “Daredevils,” Tennessee cavalry troop. In due time, orders came to march to Knoxville Tennessee, thence to Cumber- land “Gap. He was in the first field service which scouted both sides of the Cumberland Mountains, and the first battles of importance in which young Tichenor participated were Fishing Creek (Mills Spring), Tennessee; Laurel Bridge and London, Kentucky; and skirmishes at the Cumberland Gap.

Orders were received to march in the direction of Mississippi to join General Johnston’s army. On May 13, 1862, the company was re-organized and young Tichenor was elected Orderly Sergeant of Company B, 2nd Tennessee Cavalry. On March 30, 1862, they were ordered to make a forced march to protect Booneville, Mississippi. When they approached Booneville, they could see that the Federals had possession of, and were burning, the town. Just before reaching town, Col. Bob McCullough told the 125 men in the cavalry that he was going to command them and expected perfect obedience in his commands, for he proposed to recapture all the Confederate soldiers that the Yanks had taken and to save Booneville by a daring move. He ordered them into a column of twos, and they marched into Booneville facing 4,000 Federals. Onward they marched, up within fifty yards of the line of battle. Then the colonel ordered: “Halt! Left wheel into line. Right dress.” As they made no show of fright, the enemy did not fire on them, seeing that they had only a handful of men. However, the Federals soon became uneasy. They could not understand such daredevil move as had been made, marching and counter-marching, and making no show of fright. Finally the confederates who were prisoners discovered their friends and they raised such a rebel yell that it seemed to shake the ground. They considered themselves no longer prisoners. This caused the Yanks to become confused, and when someone yelled they were trapped would all be captured, this was enough. The stampede commenced . It is recorded how fearful it was to see how they ran over each other trying to make their escape. They gave a few parting shots while running, killing only six of the command. As soon as the enemy retreated, Colo. McCullough’s men dismounted and rushed to the railroad and separated the burning cars, saving most of the ammunition train and ordinance stores. The men kept up such yelling and rejoicing over the victory that the Yanks never stopped running until they reached Corinth.

The command was next ordered to go to the front, as advance guard for General Armstrong’s cavalry division. On September 14, 1862, I-Uka, Mississippi, was recaptured with an immense amount of supplies, making the men happy at the prospect of a full meal once more. However, five days later, the enemy from Corinth marched to within four miles of I-Uka and gave battle. The next day, the Confederate army retreated. AT this time, young Tichenor was detailed to take command of one division of commissary wagons and shortly afterward, near Tuscumbia, he was severely wound in battle; his left forearms was shattered, breaking both bones. His medical service was suspended for four months, until February 4, 1863, at which time he was ordered to Springhill as a recruiting officer for the 2nd Tennessee Cavalry, but soon after his arrival, it was his misfortune to have a severe spell of sickness (malaria). Before he was able to travel, the Confederate army fell back and he was left inside the enemy lines. As soon as he recovered, he recruited five men who knew every foot of ground in Williamson County. This enabled them to be very successful in all their movements. Within two months, they captured four wagon trains. Some were saved, and some were burned. Their finest sport was surprising the pickets outside Franklin and capturing a few well-equipped cavalry horses every few nights.

Their last venture, and the most successful, was when they learned that a large party of Negro slaves was going to make a break for freedom by going to the Federals at Franklin and, in order to aid the Negroes, a Federal company of cavalry was to meet them and escort them into Franklin. Knowing this, Dr. Tichenor managed, with only five men, to undertake not only the capture of the entire cavalry company, but the slaves as well. What he did was to station his five men at various distances on each side of a stone fence on the turnpike road between Springhill and Columbia, Tennessee. He placed them in a triangular position on each side of the turnpike and waited for the arrival of the Federal cavalry. IT was his plan that as the cavalry came into the area, each man behind the fence acting as a captain, would call “halt” and demand their surrender. This occurred after the head of the column was abreast of Capt. Tichenor. He commanded them to halt, surrender, and dismount, and the same command rang out in distant tones from each side of the stone fence. The Federal captain called out, “Don’t shoot. We will surrender.”

They all dismounted and laid down their arms on the side of the road. Tichenor then called to the Federal sergeant-major to take the horses, and ordered his command to remain in their places, and instructed that five men be detailed from the troops alleged to be behind the fences. The five men mounted the captured horses, and Dr. Tichenor gave orders from the prisoners to march forward by fours and keep in the middle of the road. He talked to them kindly, telling them they would be treated well if they obeyed orders. All went well until one soldier broke for liberty. He was quickly shot and left on the road, and there were no further attempts at escape. Just before arriving at Columbia, they met the Negroes with wagons and teams loaded with their plunder. Capt. Tichenor halted them told them the Rebs had captured of forty men, forty horses (all equipped), 50 Negro slaves, and five wagons and teams. The Federal captain was asked how many Rebs he had seen. He replied, “I have seen only six, but on each side of the fence, we left behind not less than a full regiment, judging from the number of officers who called out for surrender.”

During the war, simultaneously fighting and studying, Tichenor passed the examination of the medical board and was appointed acting assistant surgeon for the Confederacy. He spent much of his time trying to concoct an antiseptic fluid which would sterilize and help heal wounds. He finally fulfilled his dream. He often proclaimed: “I will use my antiseptic freely on Southern soldiers, but want no damn Yankee to get it.” He is credited with introducing the first use of antiseptic surgery in the Confederate army.

Capt. Tichenor was wounded in November, 1863, and by the time he was taken from the battlefield to the army hospital in Memphis, his leg wounds had become gangrenous, and the army surgeons ordered amputation. He protested and, with the assistance of friends, was smuggled out and taken to a friend’s private residence. He treated himself with his antiseptic solution and succeeded in saving his leg. While he was recovering from his wounds, he met his wife, Margaret Ann Drane, who with her father, the Rev. T. J. Drane, was assisting in caring for those disabled in the hospital. The couple was married in Liberty Baptist Church in Liberty, Mississippi, on November 12, 1863.

Shortly before Memphis was taken by the Federal army, Capt. Tichenor was ordered to act as Provost Marshall for Canton, Mississippi. Here, as his last duty, he was able to recruit a few loyal men for the Confederate army.

The doctor’s war record is outstanding. He participated in 24 engagements and was wounded four times – Corinth, Mississippi, and at Denmark, Meden, and Bolivar Tennessee. After the war, for the amazing price of $1.00, he bought a plantation called “Black Hawk”, and began his private practice of medicine in nearby Canton, Mississippi.

In 1868, Dr. Tichenor left his wife and two children with her parents in Liberty, Mississippi, to prepare a home for them in Wilkinson County, 45 miles south of Natchez later known as Wakefield Landing. Once a month, he journeyed alone on horse back, taking as much as three days to travel over hills, with no roads through swamps and over rivers with ferries, to see his family. It was while he was practicing in his Wilkinson County home that he began to bottle his antiseptic solution for sale.

In 1872, “the big island” in the Mississippi River between Adams County, Mississippi, and Concordia Parish, Louisiana was the rendezvous point for a group of outlaws. A certain Mr. Murrell was a desperate Leader who was uniting all dissatisfied elements for the purpose of establishing a utopia by means of murdering the owners first, and then dominating the cities. Capt. Tichenor, at the head of selected men recruited in Natchez, defeated and dispersed Murrell’s army in a battle about 35 miles below Natchez. For this service, he was delegated as surgeon for disinterring and burying the remains of Jefferson Davis in Richmond, Virginia.

In 1877, he moved to Red River Landing, Louisiana. Here he applied for a patent for the label of his antiseptic solution, which was granted on May 1, 1883. It featured the familiar battle scene. The formula was not registered, known only to him. He described the medication as a cooling medication or a “refrigerant”. In 1885, he moved to Baton Rouge and devoted his time to the manufacture and sale of the antiseptic and the practice of medicine.

Dr. Tichenor was primarily a doctor; however, his interests were varied and his accom- plishments many. While living in Baton Rouge, along with Drs. Richard Day and Thomas Buffington, he perfected a method of grafting and uniting the ulnar and radial arteries of a mill hand of Burton’s sawmill, a medical accomplishment considered impossible at the time. This in fact must have been the first limb re-implantation and vascular anastomosis. Alexis Carrel’s renowned work was not until the early 1900’s.

Dr. Tichenor’s contributions to medicine were many. He was famous for his mass grafts and was reported to be the first man to make an artificial anus in a newborn with an imperforate anus. He allegedly was the first to successfully treat spinal meningitis and was the discovery of permanganate of potash for snakebites. He invented the first inhaler (U.S. patent #87603). (However, I have been told by a knowledgeable source that a Dr.J. Nott in 1848 invented an inhaler, which would have preceded Dr. Tichenor’s).

He was a practicing photographer, first as an amateur and later as professional. He discovered the “pearl type” photographic process, which was a vast improvement on the old daguer- reotype process. He painted beautifully in oils. He was a musician and played the fiddle. Because of the war injuries to his left arm, he could not hold the fiddle in the orthodox manner. So he tied a string to the tailpiece button,looped it over his neck, held the fiddle guitar-style and bowed vertically.

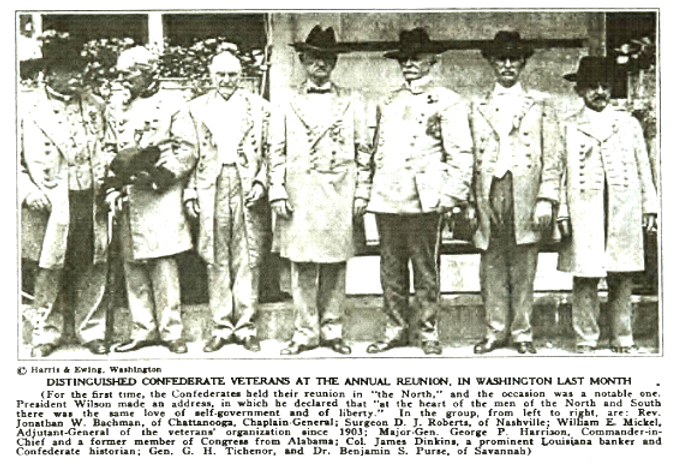

Long after the war was over, Dr.Tichenor maintained an interest in the affairs of war veterans. He organized the Medical Officers Army and Navy of Confederacy Association for the purpose of preserving medical data andthe military practice of medicine and surgery.

For many years, he was commander of the Confederate States Calvary Association and

Surgeon General of the Louisiana Division. He was also surgeon on the staff of various commanders-in-chief of the national associations, exerting his influence in the compilation of southern history, literature and chivalry, being chairman of the committee to erect a monument to women of the south, the only country to officially honor its womanhood.

He reviewed President Roosevelt’s “Rough Rider’s” before they embarked for the Spanish -American War, and his opinion as to the preparedness of these men was given to Secretary Daniels aboard the presidential yacht before the United State’s entry into the war.

Dr. Tichenor’s father was a steamboat owner and captain; hence, as a child he was exposed to the river and he maintained interest in boats and waterways throughout his life. The overflowing river ruined financially when he was s practicing surgeon at Red River Landing and forced him to move to Baton Rouge. This experience was very instrumental in his fight to control the river.

Dr. Tichenor was named “the man who conquered the Mississippi River”. Due to his study of this and other singular rivers, he is credited with changing the engineering policy of the U.S. Government, opening the southwest passages and the building of the spillway as opposed to the all-levee fallacy. He advocated these changes persistently in the New Orleans and St. Louis newspapers, waterway journals, and before various engineering press and state legislative bodies. His persistence in the development of the spillway is probably his greatest single accomplishment. Because of this, those of us living in areas below sea level are able to stay dry.

Dr. Tichenor’s name lives on through his antiseptic solution. The rise and fall of patent medicines seems to be spectacularly meteoric. One day, radio and newspaper commercials speak of nothing else. The next day, they are forgotten. It takes an outstanding man to produce and outstanding product, and Dr. Tichenor proved that he was outstanding in more fields than one. The formula has not changed and does not deteriorate. An old bottle has the same potency as a new one.

There have been over a billion bottle of Dr. Tichenor’s sold. It has become a household word as the number one all-purpose remedy in many southern areas. The older label promoted the formula for wounds, burns, bruises, sprains, bruises, colic cramps diarrhea, and flux—and for colic and blots in horses and mules. The label later claimed its use for sunburn, minor throat irritation, sprains, bruises, sore muscles, sore and tired feet and athlete’s foot, insect bites, scratches or other minor injuries, superficial burns, scald, prickly heat and toothache. Today, the label’s only directions are as a mouthwash and topical antiseptic.

It was noted in the 1960’s’ that a large number of New Orleans blacks who make up over 50% of the Tichenor market, had moved to Chicago and carried with them their loyalty to the brand and demanded it. Hence, the stores had to stock it. However, other forays into Yankee territory proved to be a big flop, thereby fulfilling the good doctor’s ancient curse-prophecy, that he did not want a damn Yankee to get it.

During prohibition, Dr. Tichenor’s antiseptic proved a good liquor substitute, so the government cracked down on the alcohol percentage and for a time required that additional ingredient be added that would discourage oral intake.

Market research showed that most people using Dr. Tichenor’s antiseptic were elderly and black.

So a decision was made to change the old bottle label. The depicting a Revel soldier triumphantly waving a Confederate flag was shrunk, while the flag and its non-too-subtle message were obliterated by a small banner reading “Kills germs – helps heal.” This was in 1965, the year of the Selma, Alabama, civil rights march. One year later, the scene was dropped altogether. Meanwhile the word refrigerant went the way of all pseudo-medical archaisms.

In order, to get to the young market, a radio personality, Pinky Vidacovich, was hired to

make ads with singing commercials which always ended up “Good old Dr. Tichenor,

best antiseptic in town.” He said this with a Cajun accent.

In 1886, the business was moved to the foot of Canal Street in New Orleans, the gateway to the recent infamous New Orleans World’s Fair, and in 1962 it moved to its present modern plant.

In, January 1923, Dr. Tichenor, at age 85, was seriously injured in a fall. He died three weeks later. His body was brought back to Baton Rouge where funeral services took place aboard a train. Thus ended the multifarious life of the best-known southern surgeon.

.............................................................................................................................................................................

Source

The Times-Picayune (New Orleans) 12Jun 1898 Sun. Page 10

THE NEW ASSISTANT SURGEON GENERAL

Dr. George H. Tichenor has been honored with the appointment of the assistant surgeon general, U.C.V on the staff of General E.H. Lombard.

The subject of this sketch is a native of Kentucky but removed to Nashville, Tenn. in 1859. He entered the Confederate service in that state by joining the Williamson Company Dare Devils, on June 6, 1861, commanded by Captain Wm. Ewing.

On June 10, 1861, his command was ordered to Nashville, Tenn., where a battalion was formed and elected F. N. McNary, Lieutenant colonel, and commander of Second Tennessee Cavalry. In due time orders came to march to Knoxville, Tenn., thence to Cumberland Gap. Their first field of service was scouting on both sides of Cumberland mountain, and the first battles of importance in which Dr. Tichenor participated, were at Fishing Creek, (Mill Springs), General Zelicoffer commanding until killed; Laurel Bridge, Ky., Sept 28, 1861; a running fight at Lebanon, Ky., Sunday, Sept 29, 1861; and Oct. 23, 1861. Also, a skirmish at Cumberland Gap followed. On Oct. 31, they had an engagement at Creavesburg, on the Cumberland River, with the federal infantry. Then on Dec. 26, 1861, the battle of Jamestown, Ky.

Orders were then received to march in the direction of Mississippi, to join General Johnston's army, re-enforcing as the sequel proved, Corinth and the Mississippi Department. They were instructed to look after Eastport, on the Tennessee River, and there had frequent engagements with the federal gunboats. On Sunday, April 6, 1862, the command was ordered into line of battle on the hills below Eastport, between the river and Iuka, Miss. On April 13, 1862, they engaged in the battle of Bear Creek bridge and railroad bridge, defending the same.

May 13, 1862, the company re-organized when young Tichenor was elected orderly sergeant of Company B, Second Tennessee Cavalry. May 30, 1862, ordered to make a forced march to protect Boonville, Miss., Captains Parrish, Martins and McKnights, three companies in all, were moved rapidly to the rescue of Boonville. When they approached near Boonville, they could see that the federals had possession and were burning the place. Just before reaching town, Colonel Bob McCullough came dashing up and commanded: "Halt? Front face! Right dress." "Attention, men; how many have we?" "125, all told." "I am going to command you, and all depends on perfect obedience to my commands. You are not to raise a gun, pistol, or saber until I order you. I propose to re-capture all of our men that the Yanks have taken and save Boonville, by a daring move." "By twos, left wheel into line==march." In a few minutes, we were marching into Boonville, facing 300 to 5000 federals. Onward they marched, up to within fifty yards of two lines of battle. "Halt! Left wheel into line; right dress." As they made no show of fight, the enemy did not fire on them, seeing that they had only a handful of men. However, they soon manifested uneasiness; they could not understand such a dare-devil move as had been made, marching and counter-marching and making no show to fight. Finally, the Confederates who were prisoners discovered their friends and they raised such a yell that it seemed to shake the ground. They considered themselves no longer prisoners. This caused the "Yanks" to become confused, and when someone yelled out, "We are trapped and all will be captured," this was enough; the stampede commenced. t was fearful to see how they ran over each other, trying to make their escape. They gave a few parting shots while running, killing G.A. Calwell, of Company B, and wounding five of the command. As soon as the enemy retreated, Colonel McCullough's men dismounted and rushed to the railroad and separated the burning cars, while the bombshells were flying in every direction from them, saving most of the ammunition train and ordnance stores. The men kept up yelling and rejoicing over the victory, planned by "Uncle Bob." the "Yanks" never stopped running until they reached Corinth. Lieutenant Colonel C.R. Bartau, commanding the Second Tennessee Cavalry, was complimented, as well as the entire command participating in the daring move, which accomplished so much for our retreating army. In the depot, there were a dozen or so helpless, sick, and wounded Confederates. It was a fearful sight to see the number of men cremated, in the stations and under the station house, and no one able to get there to pull or drag them from the burning building.

The command was next ordered to go to the front as an advance guard for General Armstrong's division of cavalry. On Sept. 14, 1862, Iuka, Miss., was captured by Armstrong before Price's army arrived. An immense amount of supplies were captured making the men happy at the prospect of a full meal once more. On Sept. 19, 1862, while at Iuka, the enemy from Corinth marched out within four miles of Iuka, and gave battle, killing General Little. On the 29th of September, General Price ordered the army to fall back. Young Tichenor was then detailed to take charge of one division of commissary wagons. General Price sent orders to hurry up the train. The men, after their hearty meal, were very slow and Young Tichenor repaired to headquarters as quick as hE could, and said, "General, if you will order a shell thrown into the wagon camp, I guarantee the train will move in thirty minutes." "Thank you, orderly, I will do it." In a few minutes, bang! bang! was heard and when the smoke was cleared from the bursting shell, the teamsters got a first-class move on them, and in a few minutes, all the trains were out on the roads considered safe.

Oct. 5, 1862, the command was in battle near Tuscumbia. Oct. 9, 1862, the subject of this sketch left camp, being wounded badly, and his military service suspended until Feb. 4, 1863. On that date, he reported for duty to Colonel C.R. Bartau at Okolona. His orders were to rest quietly until he could hear from Richmond. On Jan. 8, 1853, a commission had been issued to him and he was ordered to middle Tennessee, as a recruiting officer for the Second Tennessee Cavalry. The order was from Colonel Bartau, and approved by the Inspector General's office, Richmond. With his commission in his pocket, he started for Springhill, Tenn., and arrived on Feb. 20, 1863, in time to witness the general confusion, caused by the killing of General Van Dorn by Dr. Peters. He made his headquarters with his friend, Robert McElmore, but soon after his arrival, it was his misfortune to have a severe spell of sickness. Before he was able to travel, our army fell back and he was left inside of enemy lines. As soon as restored to health he called a number of our boys together and submitted plans for equipping all who would join him and at the same time do good service. They readily consented. His men, knowing every foot of ground in Williamson County, enabled them to be very successful in all of their movements. Inside of two months, they captured four wagon trains; some were saved and some burnt. Their finest sport was running the pickets into Franklin and capturing a few well-equipped cavalry horses every few nights. Their parting respects to the federal army, stationed at Franklin, Tenn., was on learning that a large party of nrgroes was going to make a break for freedom, by going to the Federals at Franklin, and in order to aid the negroes a company of cavalry was to meet them and escort them into Franklin; knowing the night, Captain Tichenor managed to get only five of his men to agree to undertake the capture. When the time came, it was a favorable night for executing his plan. They stationed themselves on each side of a stone fence on the turnpike road, between Springhill and Columbia, Tenn. He placed his men in a triangular position, on each side of the turnpike, and waited for the arrival of the federal cavalry. It was the captain's plan to call a halt, and demand their surrender, and each man along the line was to demand the same, with a like command. They waited until 11 p.m. and were rewarded for their patience by hearing the horses' feet and rattling of the sabers. As soon as the head of the column was abreast of Captain Tichenor he commanded them to halt, surrender, and dismount. The same command rang out in distinct tones from each side of the stone fence. The federal captain called out, "Don't shoot, we will surrender." Captain Tichenor commanded them to dismount, lay their arms on the side of the road, and form fours. He called to his sergeant major to take the captured horses; then ordered the command to remain in their places, and instructed that five men be detailed from the troops supposed to be behind the fences. His horses were brought up, having been held by one man, and they mounted when he gave the order for the prisoners to forward by fours and to keep in the middle of the road. He talked to them kindly, telling them he would treat them well if they obeyed his orders. All went well until one of the prisoners broke for liberty. He was quickly shot and left on the road, and they had no more trouble. Just before arriving at Columbia, they met the negroes with wagons and teams loaded with their plunder. Captain Tichenor halted them and told them the "rebs" had captured their friends, and now to turn around and go back to Columbia. They hesitated when he commanded them to obey or he would fire on them. They obeyed in quick order when they saw the federal prisoners. They arrived in Columbia just as the sun was rising. It was not long before the town was aroused and out in full force to witness the night's work of six men. Captain Tichenor was sent back to secure the federal arms left on the roadside and they were brought in. The result of this daring venture was the capture of forty men, forty horses, all equipped, fifty negroes, and five wagons and teams. The federal captain was asked how many "rebs' he had seen. He replied: "I have only seen six, but on each side of the fence we left behind not less than a full regiment, judging from the number of officers who called out for surrender." Captain Tichenor then returned south, to Canton, Miss., and was discharged from the army, because of disability of wounds, and married Nov. 12, 1863. During the month of January 1864, a special order was issued, instructing that all able-bodied men should go into the army, and the wounded soldiers should go into the community and quartermaster's department,. Captain Tichenor was ordered to act as provost marshall for Canton, Miss. This order was obeyed, and it was the means of recruiting our army with a few men who were very loyal.

During the war, Dr. Tichenor was wounded four times. It was his great fortune to possess money enough to pay, and secure the very best entertainment and attention when sick or wounded. He gave considerable attention to our hospital service; being a chemist and medical student licensed to practice. His opinions were respected by those he came in contact with. Soon after the close of the war, Dr. Tichenor came to Louisiana and for many years successfully practiced his profession at Baton Rouge and elsewhere. Later he came to New Orleans and has always been prominent in Confederate veteran circles, being the commander of camp No. 9, Confederate Veterans' Cavalry Association, for a number of years in succession. When General Lombard was elected major general of the Louisiana division of United Confederate Veterans, Dr. Tichenor was appointed surgeon general on his staff.

Sorting Out Fact from Fiction

(Family traditions and oral histories sometimes are a little flawed)

THE REAL STORY

VARIOUS PHOTOS

G.H. TICHENOR HOUSE - LIBERTY, MS.

G.H. TICHENOR OFFICE - LIBERTY, MS. ABOVE & BELOW

G.H. TICHENOR HOUSE - LIBERTY, MS.

G.H. TICHENOR THROUGH THE YEARS

DR. TICHENOR & DR. YOIST

POINTE COUPEE PARISH, LA.

(NOT VERIFIED)

“Club Men of New Orleans”

1917 – Presented to Margaret Jerome Tichenor, granddaughter

(Mrs. Russell G. Heyl)

Born Jan. 24, 1917

(Book in Possession of Heyl family

.jpg)

FROM INSIDE COVER - To Margaret Jerome Tichenor 1917.

Thomas J. Tichenor

Brother of George H. Tichenor

Birth: Feb. 6, 1839

Death: Dec. 13, 1877

Thomas Tichenor was born to Rolla and Elizabeth Humphrey Tichenor in 1839 in Ohio County, Kentucky. Thomas was handicapped and never married. He apparently followed his bother and lived most of his life with him and his family.

He received jointly with his brother a lot of land of about 37 acres in McLean County, Kentucky from the estate of their grandfather, George Humphrey, in 1860.

He died in the yellow fever outbreak at age 38 which also took the lives of his two nieces and one nephew. He resided at that time in the home of his brother and sister-in-law at Red River Landing, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana.

Margaret Ann Drane

Mrs. George H. Tichenor

Confederate Spy

Margaret was born on August 4, 1846 in Brecken-ridge, Kentucky, the fourth child of Rev. Thomas Jefferson Drane and Margaret Thurman. Margaret died from a gastric hemorrhage aboard a train on her way to Hot Springs, Arkansas on November 8, 1924 about two years after the death of her husband.

Her father, being a popular Reverend, never stayed in one place for a long period of time and as such, the family seemed to be always on the move. (Family details to follow)

In 1860, at age 16, Margaret was in Memphis along with her Sisters Mollie and Sallie and brother, Robert Larue. Once Memphis was in peril, the family fled to Canton, Mississippi. Mollie Smith was still in Memphis, and Margaret went to help care for her as she was not well. Margaret was engaged in treating wounded soldiers and it was then that she met Captain George Tichenor who had been sent to Memphis to recover from a gunshot wound. They married on November 12, 1863, back in Canton, Mississippi.

Margaret and George would have seven children with only three sons surviving to adulthood.

....................................................................................

Source: James Anthony Drain/Drane Md.Ky.Tn By Shirley Lewis April 13, 2001 (Entire post following)

The writer of this history (Dr. George Humphrey Tichenor Jr.) remembers many stories told by his grandmother, Thurman, concerning this section of Kentucky. How one of her ancestors was the first supervisor of mails and the trials encountered not only with the Indians but also with robbers, the mail being carried by relays on horseback before the stage coach made its advent. Also, tales told the children of Indian scalping and fights in this section by mother, Margaret Drane, which invariably made our hair stand on end and bed a doubtful place of safety, especially as they were true to family tradition. How great uncle, Col.. Whitley, a famous Indian fighter, saved one of the Vanatter family Col. Lewis after being scalped by the Indians. (the Vanatters were bankers in Shelbyville. I knew some of the family, related to the Timberlakes of Louisville, KY. by marriage, Sam Lawrence who lived there also was a cousin of my mothers.)

My mother was Margaret Ann Drane, both grand-parents, George Drane and Philip Thurman were Messmates at the Battle of Chalmette, New Orleans under General Jackson, War 18112. According to grandmother Thurman, these friends, comrades in arms, laid a trap to unite their families by marriage by Geo. Drane sent his son, T. J. Drane, with a supposedly important letter to Philip Thurman’s home where he met Margaret Thurman, fell in love, and later married.

Original Photograph in possession of the Heyl family (above)

Margaret Ann Drane is the daughter of Thos. Jefferson Drane and Margaret Ann Thurman, granddaughter of Geo. Drane (whose sons were Dr. William Whitley Drane, Rev. Thos. Jefferson Drane, and James N. Drane, daughters, Martha and Mary) , and wife Julia Whitley, (daughter of Col. Whitley, Indian fighter). (Mrs. William W. Drane was a Board. Dr. Milton Board of Louisville, KY states that his father Judge Board knew Geo. Drane very well in a letter to Mrs.. B. R. Warder of Bowling Green, KY, however, my mother says the only thing she remembers about his was that she was a child when he visited them and he was very old). a great-granddaughter of Washington Drane of Shelbyville, KY, or rather the neighborhood, and Miss Lawrence.

Margaret Drane, Wife of Dr. Geo. Humphreys Tichenor, Sr., daughter of Rev. T. J. Drane and Margaret Ann Thurman was born in Breckenridge Co. KY, Aug 4 , 1846, Received her education at the Baptist College at Shelbyville, KY and the State college at Memphis, TN. During the Civil War, her principal service done for the Confederacy was assisting her sister, Mrs. Mollie J. Smith to enable eleven of Forrest's soldiers to escape from the Memphis prison and carrying messages into Memphis TN, through the lines to be forwarded to Gen. Braxton Bragg in KY.

During Reconstruction, her experiences have been told by Mrs. A. S. Dimmitry (?) War- Time Sketches, under her own name and the nom-de-plume Thurman. While living in New Orleans, LA, she has been a scribe in Confederate affairs and was President of the New Orleans Chapter, No. 72, U.D.C., and for three years Corresponding Secretary of Jefferson Davis Morial Assn.

While a member of the Stonewall Jackson Chapter, she opposed the McKinney design for the Women of the south which had been accepted by the Veterans for the reason that she considered it did not correctly portray the heroic southern woman. She convinced her chapter, the U.C.V., U.D.C., and C.M.S. Assns and they withdrew their endorsement of the design. During her vigorous campaign, she received numerous letters from prominent men and women leaders of the old and new South. These letters and articles written by her were incorporated into a book and deposited in the Solid South room, Confederate Memorial, Richmond VA.

These letters and articles comprise a basic work for the historian and future novelist in regard to the true character of the Southern woman of the Sixties. She was made a life member of the Confederate Memorial Literary Society, Sept. 5 1911.

She has three living sons, R. A. Tichenor, Atty. and Notary Public, Dr. G. H. Tichenor, Jr., New Orleans, La, and Dr. Elmore Drane Tichenor, Detroit, Mich.

......................................................................................................................................................................

Source:

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans) Sun. May 7, 1911 page 18

MRS TICHENOR REPLIES TO GEN. WALKER ABOUT CONFEDERATE WOMEN MONUMENT

Mrs. George H. Tichenor has written the following to the Times-Democrat regarding the monument to the women of the Confederacy.

1917 Palmer Avenue, New Orleans, La., April 28, 1911.

To the Editor of The Times-Democrat:

We must confess to some surprise on opening the pages of The Times-Democrat of April 4, to find that we were not only pilloried in its columns for expressions of opinion regarding a matter of general interest but also recognized the fragments of a certain letter there given to the public, which was never prepared for the press. Since Gen. C. Irvin Walker has seen fit, without consulting the writer's wishes, to the public part, it is to be regretted that he did not print the letter in its entirety.

It is unfortunate that Gen. Walker when inditing his communication to the papers, had not at hand the U.D.C. Year Book of the Gulfport convention, 1906, with which to refresh his memory upon, certain points. Had he been so favored, we doubt if he would have written the following: "We cannot, for one moment, suppose the U.D.C. would officially condemn the means our committee has taken to honor the women whom they have said should be honored when those in charge of the grand work had not invited such an expression of opinion."

Here, surely, is a lapse of memory. In his own address at the convention, after inviting the co-operation of the U.D.C., he frankly says (page 13): "We desire this unity of action to be shown by the United Daughters of the Confederacy officially endorsing our proposed memorials to women of the Confederacy.

Gen. S.D. Lee (page 15), in a letter read before the convention, also says: "... Your indorsement alone of the monument will do much to ensure success."

If words mean anything, is it a matter of marvel that, in their simplicity, the daughters really believed they were invited to ab official endorsement and were entitled to an expression of opinion upon a question so near their hearts? Certainly, they would have been silent had they not thought this right might be exercised without forfeiting that modesty which is woman's chiefest crown, and which must be inherent, since they received it from the mothers whose fair fame and works a monument I proposed to commemorate.

We frankly admit we have never been honored by seeing the original Kinney design. Its "counterfeit presentment" in the "Veteran" is the only glimpse we have had of what is considered by Gen. Walker a "most appropriate, emblematic and artistic design..... superior to thousands of other monuments." We doubt very much if many outside of the General and his committee have been more highly favored than ourselves; but surely, the representation in the Veteran must have been authoritative, else why given to the public in the official organ of the U.C.V.? Again, in the candor of our nature, and without claiming super sensitiveness upon questions of art, we must confess that the "high artistic and emblematic form" of the model did not thrill our soul; did not impress us as worthy of the object claimed by Gen. Walker--"to truly honor the women." To our dim eyes, it wholly lacked the inspiration which the theme held for genius.

Ge. Walker states that "it is far better to have the design you disapprove than nothing." Right here we raise the issue. Is it fair dealing with the future to pass on a false conception of the noble Confederate women? Is it fair to ask the Daughters of the Confederacy to sit silently by and see their great mothers handed down in a group, of which none of the parts, singly or collectively, in form, act, character, is representative of them or of the time? Is it fair to ask their co=operation in building a monument of which they cannot approve? Looking back upon our ancestry and forward to posterity, we indignantly refuse for our dead mothers and for ourselves to be represented by what is known as the "Kinney design." Can anyone looking upon it believe that it will keep alive the proud story of Confederate womanhood and Confederate valor?

We can bear with equanimity the dire alternative so feared byGen. Walker, "that if the present monument does not culminate in success, the immortal heroines of our women will remain forever unmarked." Far better forever remain unknown than falsely certified to by a monument that suggests nothing of their "immortal heroism."

That the Kinney design was not regarded with favor by the late U.D.C. convention at Little Rock is clearly proved by the motion of a distinguished daughter of Georgia being adopted. We take this motion from minutes of the convention (page 108); "Miss Rutherford of Georgia moved, as a substitute to Mrs. Tichenor's motion, that a loving message be sent to the United Confederate Veterans, in appreciation of their desire to honor the memory of our mothers of the sixties; that, while Miss Kinney may be an artist of great ability, we do not approve of the design she has admitted for this monument to be erected by the veterans."

Upon every question, there is always a "for" and "against." Therefore we cheerfully admit that several members of the U.D.C. have asked: "Is it courteous to raise an objection to the monument since it is a tribute from the veterans to the war women?" Here again, we must take issue with our dissenting sisters, as well as Gen. Walker when he remarks that those "in charge of the grand work had not invited such an expression of opinion from the U.D.C." on the ground that upon whatever touches the honor and glory of their mothers it is the special privilege of the daughters to have an opinion and give it full expression. This natural right was sustained by a delegate from Virginia in support of the Tichenor resolution at the recent Little Rock convention. She furthermore claimed that "the veterans have asked us to raise money for this monument, as it is a monument to our mothers. Therefore we have a right to express an opinion." We much regret that we have not the various yearbooks to consult, but a reference to the minutes of the Little Rock convention, page 108, will show that in Richmond, New Orleans, and Gulfport our approval of a monument has been asked.

Gen. Walker states tha the committee "are bound by" their "contract as well as their own wishes to fulfill its obligations, and they propose to do so." If the fulfillment of the contract means the erection of this monument like duplicate paperweights in the cities of the South, does not this boast, considering the mutability of all earthly things, seem a trifle arrogant? It looks very much as though the U.C.V. as an organization had not the unbounded confidence in the infallibility of judgment assumed by Gen. Walker for himself and committee, since Gen. Geo. W. Gordon, in reference to this monument, declared through General Orders No. III, section3:

"Indeed, we have been assured upon the good authority os a veteran that no U.C.V. convention has ever accepted or approved the Kinney design, but has only recognized Gen. Walker and his committee as having charge of the work."

In a recent issue of a New Orleans paper is given a design for the Southern women's monument which, it is claimed, was accepted by the committee in charge. This design, while similar, yet differs materially from the one adorning the pages of the Veteran. The conflicting statements as to which or what design has really been accepted leaves the matter considerably in doubt, yet, there is sufficient similarity in the two designs given to the public to indicate what we can expect if Miss Kinney's ideas are adopted. If the design had been accepted officially, as Gen. Walker states, why this change"

This new version of the design cannot fail to remind one of the death agonies of the Laocoon. A more repulsive figure to be put before the world as a representative of the soldiers and causes that "died on the field of glory" it is impossible to conceive. If our friends, the veterans, are content in the shrouded guise to be cast in enduring bronze--that is for themselves to decide. The huddled form, the impassive, meaningless star of buxom Fame may rejoice the hearts of those who delight in allegory and can be endured by others who differ. But our protest against the figure called "The Southern Woman" is as vigorous as ever. Her position and attitude are alike objectionable, and her teasing tickle of the dying soldier's chin may be "highly artistic and emblematic," but we think it will strike the average observer as both flippant of thought and indecorous in action. It is neither representative of the dead mothers of the Confederacy nor of their daughters who survive them.

We take our leave of Gen. C. Irvine Walker and his monument in the words of a noble Virginia matron and honored Daughter of the Confederacy, who did much to keep this grotesque design from dishonoring Virginia womanhood:

"As the daughters of our mothers, we protest against any job lot of monuments, such as this one, to be placed in any State of our Southern Confederacy."

Mr. Geo. H. Tichenor

A Woman of the Sixties.

.....................................................................................................................................................................

Source:

The Times-Democrat (New Orleans) 14 Dec. 1913, Sun page51

A Toast

We are indebted to the courtesy of Mrs. Gerge H. Tichenor for the following clever bit of verse from the pen of Mrs. Eugenie Clark Clough, a gifted daughter of er of Kentucky and kinswoman of Mrs. Tichenor.

Mrs. Clough is the author of the poem, "The Little Bronze Cross; an Appreciation of Stonewall Jackson," another on Robert E. Lee, and other literary works familiar to all educators and Daughters of the Confederacy.

(Written in the gust book at Begue's))

We drink to the old Creole City

(Its charm ligers sweeten the air)

To its romance, its olden-time splendor,

To its chivalrous men, brave and tender;

To its women--the fairest of fair!

Eugenie Clough

NOTE: The five sketches below were relayed to Adelaide Stuart Dimitry, author of War Time Sketches (1910) by Margaret “Maggie” Ann Drane. The older sister of Margaret was Mary “Mollie” Juleana Drane Smith – married to Maj. James Hammond Smith on December 1, 1857 in Memphis when he was 23 and she was 18. They worked “underground” during the occupation of Memphis.

Margaret actually went to Memphis to help care for Mollie who was suffering from ovarian cancer (per Drane family Bible), passing away in January, 1869, seven months after the birth of her second child. After Mollie’s death, James would marry Emily Jane Wright in Memphis in 1870. He brought into this marriage two small children adding three more with Emily. He and Emily had a long life and he retired as a banker. In 1921 at age 86, he fell off a chair which ultimately led to his death (per Death Certificate)

Mary "Mollie" Juleana Drane Major James Hammond Smith

For some reason, Margaret used her mother’s maiden name (Thurman) in relating the story about reconstruction (Page 83 below). Only the stories involving Margaret follow.

Source:

Drane Bible

January 17, 1869

Died, on the 8th of January, 1869 of Ovarian Tumor, Mrs. Mollie J. Smith, daughter of Elder T.J. and M.A Drane of Isyka, Miss., aged 28 years, four months and 23 days. Deceased had been the subject of deep and severe afflictions for 9 years previous to her death, and confined to her bed the last five months of her earthly existence, during which time she was never heard to utter onr murmuring word. Her Bible was her inseparable companion, and as she gradually declined in physical strength, her mental powers assumed their wonted energy, and from day to day her confidence in her acceptance with her Redeemer increased; conscious that the hour of her departure was at hand, she bade adieu to her family and friends, said “weep not for me, death has no terrors, I fear not the grave, I shall soon be with my Savior in heaven,” then sang in a clear voice—

“Jesus can make a dying bed

Feel soft as downy pillows are,

While on his breast I lean my head

And breathe my life out sweetly there.”

The writer has seldom if ever, witnessed a death so calm; with more composure, or more triumphant, “Thanks be to God,” who giveth us victory “even in death,” and that we “sorrow not as those who have no home.”

D.

......................................................................................................................................................

Source:

Who's Who in Tennesse

Memphis https://tngenweb.org/whos-who/smith-james-hammond/

SMITH, James Hammond, banker; born Shelbyville, Ky., July 6, 1835; German descent; son of Abram and Margaret (Campbell) SMITH; his father was a member of Capt. Ford’s company under Gen. Andrew Jackson, and was in the battle of New Orleans during war of 1812; his paternal grandparents were Daniel and Abigail de la Saint Moir SMITH, who immigrated to the United States from near Frankfort on the Main, Germany, in 1790, settling in Virginia; educated at Shelby College under Rev. William I. Waller; after his school days were over he served as deputy clerk under W.A. Jones, clerk of the Circuit Court, for six years, and in 1857 removed to Memphis, Tenn., and served as deputy sheriff of Shelby Co., Tenn., four years under James E. Felts; he was assistant provost marshal under Gen. Bragg at Memphis until that city was captured by the United States forces; after close of war he was engaged in the grocery and cotton business for some years; served as member of the city council during 1871-1872-1873 and was secretary and treasurer of the Howard Assn. during the terrible yellow fever epidemic of 1878, during which time more than six thousand of the citizens of Memphis died; the Howard Association had at the commencement of the epidemic thirty-three members during the epidemic eleven of their number died, and every member but four was stricken down with the fever, Major Smith being the last one; as treasurer he received in donations over four hundred thousand dollars, in addition to a large number of cars of supplies of all kinds; in Keating’s history of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 is published a full and complete list of the donations received by him, giving name, date and amount by state, also a list of the dead, giving name and date of death; in 1879 he was elected as one of the members of the State legislature, serving as such during 1879, 1880, 1881 and 1882; in 1882 he was elected secretary and treasurer of the Pratt Coal and Iron Co., Birmingham, Ala., at that time the largest coal mining plant in the South; during 1882 he was appointed postmaster of Memphis, Tenn., which position he held during Arthur’s administration and the early part of Cleveland’s; in 1887 he organized and was cashier for some eight years of the Memphis National Bank, and also the Memphis Savings Bank; in 1889 he organized the People’s Savings Bank and Trust Company, and has been the active manager of same up to the present time; he has been prominently connected with the Republican party since 1870, represent his party as delegate both to State and National conventions from his county and congressional district, for more than thirty-five years he has been deacon of the Linden Street Christian church of Memphis, Tenn; married Emma J. WRIGHT in June, 1870.

......................................................................................................................................................

Source:

The Commercial Appeal (Memphis) Thu. Jun 16, 1921 page 4

MAJ. J.H. SMITH ILL.

Suffering From Nervous Shock, the Result of a Recent Fall.

Major James H. Smith is seriously ill at his home, 242 East Georgia Avenue. Major Smith, who is 86 years old, suffering from shock, the result of a fall about 10 days ago. While he sustained no broken bones in the fall, the shock was too much for his weakened nervous system. Major Smith came to Memphis in 1857, and since that time has been closely identified with the city's interests, having held prominent positions in several lines of businesses. He organized and built up three splendid banks and was serving as postmaster when the present post office was built. He was identified with the Howard Association and did splendid work during the yellow fever epidemics.

......................................................................................................................................................

Source:

The Journal and Tribune (Knoxville) Sat. Jun 18, 1921 page 3

MAJ. JAMES H. SMITH HAD LIVED MOST USEFUL LIFE

Memphian Disbursed Million Dollars During Yellow Fever Epidemic.

Memphis, Tenn., June 16--Funeral services for Major James Hammond Smith, prominent in the business, political, and religious life of Memphis for more than fifty years were conducted today from the home ne established at the close of the civil war, at the corner of Rayburn Boulevard and Georgia Avenue. He died yesterday on the fifty-first anniversary of the wedding. In his eighty-sixth year, following a 10 days illness due to injuries in a fall at his home.

Among his most notable achievements in Major Smith's career, which carried him through many very useful years, devoted to public service and business and political enterprise, was his distinguished record in Memphis during the year of yellow fever in Memphis in 1878. As secretary and treasurer of the Howard Relief Association. Major Smith handled the disbursement of over a million dollars to alleviate the suffering of fever-stricken citizens, over 5,000 of whom died and were buried during the 94 days it lasted.

As a business organizer, Major Smith's advice and services were sought prior to the establishment of the Pratt Coal and Iron company in 1880, one of the first and greatest companies of its kind which contributed largely to the growth of Birmingham, Ala., as an industrial and manufacturing center. He helped organize the Memphis National Bank and the Memphis Savings Bank.

Major Smith was born in Shelbyville, Ky., on June 6, 1836, the son of Abram and Margaret Campbell Smith.

In December he moved to Memphis where he served as a deputy sheriff for nearly four years. When the civil war broke out he was commissioned a major in the Confederate army, attached to the staff of General Braxton Bragg, by whom he was appointed deputy provost marshall at Memphis. In this capacity, Major Smith served until the city was surrendered to the federal forces in 1862.

After the death of his first wife, Mollie Drane in January of 1869, he married Emily Jane Wright on June 14, 1870 in Memphis.

Source:

The Commercial Appeal (Memphis) Sat. Dec. 31, 1932 page 5

MRS. EMILY W. MITH, CHURCH WORKER, DIES

She was born in Madison, Ind., the daughter of Capt. and Mrs.

Tom T. Wright. She received her education in the schools of

Madison and came to Memphis with her parents soon after the

Civil War.

Shortly after coming to Memphis, she met Maj. J.H. Smith, a Confederate soldier. They were married June 16, 1870, and they lived to celebrate their golden anniversary. The celebration was held in 1920 and a year later Mr. Smith died.

Mrs. Smith made her home at 242 East Georgia for more than 60 years. She moved to her new home on University Place three years ago. Her chief interest in life was her home and her children. She took a special interest in flowers and had a charming flower garden at her home.

She celebrated her ninety-fourth birthday with a party at her home on Nov. 4 and sang a song for her guests. During her early life, she sang often in the choir of Linden Avenue church.

Mrs. Smith is survived by two sons, Wright W. Smith and Horace Neely Smith of Memphis, and a daughter, Miss Donna A. Smith of Memphis; a sister, Mrs. Charles A. Moore, Los Angeles, and two brothers, J.W.C. Wright, New Orleans, and Frank W. Wright, Horn Lake, Miss. She was the grandmother of Hammond B. Smith and Malcolm Smith.

Funeral services will be held from the residence at 2:30 o'clock tomorrow afternoon, with the Rev. J. Eric Carlson, pastor of McLamore Avenue Christian Church officiating. Burial will be in Elmwood Cemetery, with J.T. Hinton & Son in charge.

Was Oldest Member of Linden Avenue Christian Church

Mrs. Emily Wright Smith, the oldest member of Linden Avenue Christian Church, died at her home, 773 University Place, at 7:35 o'clock last night, following a month's illness. ZShe was 94 years of age.

Known affectionately as "Miss Emily" at Linden Avenue Church. Mrs. Smith was one of the early leaders at the old downtown church. She took an active interest in church affairs until eight years ago when she fell and broke her hip. She joined the church in 1865.

War-Time Sketches

Historical and Otherwise

BY

ADELAIDE STUART DIMITRY

HISTORIAN "STONEWALL JACKSON CHAPTER OF NEW ORLEANS

No. 1135" U. D. C.

(1909-1911 )

LOUISIANA PRINTING CO. PRESS,

NEW ORLEANS, LA.

Page 41

THE CONFEDERATE GIRL.

PART I.

(Data for this and the two following papers furnished by Mrs. George H. Tichenor, of New Orleans.)

JUNE 3, 1861, Tennessee severed her connection with the Union. At once "Soldier Serving Societies" were organized by the ladies of Memphis for the purpose of making uniforms and clothing for our troops, and the preparation of bandages, lint, etc., for the hospitals. Old and young, matron and maid were eager to aid in a cause that appealed strongly both to their affection and patriotism. Soon the gatherings outgrew private houses and, when other buildings were not available, the churches were pressed into service for their noble work - a work all untrained, but pursued with a heart and soul that gave it life and energy.

Among the numbers that daily crowded one of these churches - turned during the week into an immense sewing-room - might be noted a young school girl, Margaret Thurman Drane by name, a golden-haired lass of fourteen with eyes of Scottish blue. Ardently Confederate, each day after school she hastily tripped to church to aid in what warm fancy and a generous heart proclaimed a glorious task - that of making garments for the brave boys already on their way to Manassas, battle field of Virginia. Her eyes must have grown large from wonder and dim from dismay when the grey uniform coat of an officer was put into her untried hands to make. Poor little lass! She knew how to hemstitch, but not how to back-stitch, and it was before the days when sewing machines were made as much a part of the household equipment as beds and chairs. However, her heart was stout and with fingers both willing and diligent, after two days of hard toil and the breakage of a paper of needles, the coat was completed. Alas! when her labor of love was scrutinized at headquarters, no fault could be found with the stitches, but it was discovered that while the front and side pieces had been laboriously sewed together, the back had been innocently left out!

Page 42

She did not receive the blue ribbon for her work that day, but was assigned the less responsible task of bringing hot smoothing irons from the basement, upstairs, to be used in pressing seams.

A new hotel that had never been used as a hostelry was converted into a hospital and the city was divided into sections, each section taking its turn at service. The mothers, with a train of household servants nursed the wounded and sick, while the young girls carried flowers, wrote letters for the convalescent soldiers and sometimes - it was told with much glee by the mischievous recipients - they again washed faces that, in the course of a day, had already received due attention by earlier visitors, at least half a dozen times - all equally solicitous of giving aid and comfort to our brave defenders. Here came our lass - most eager to help, but so little knowing how. Timidly threading the long aisle of cots, she was implored by a soldier suffering from a gunshot wound to rub his arm with liniment to cool his fever and ease its throbbing pain. Proud to be called upon, her eyes bright and face aglow from sympathy, she seized a bottle nearby and hastily poured its contents on arm and in wound - bathing, saturating, rubbing it in with all the energy of which her young muscles were capable to make sure it would do good work. "Ah! unfortunate girl!" shrieked the soldier from the cot, his agonizing pain getting the better of his chivalry. At the sound of his wrathful voice there was a sudden flutter of skirts and patter of feet, for the young practitioner fled down the aisle that seemed endless, for fear that she had killed him! We will trust that the remedy was curative - it certainly was heroic and the pungent odors of turpentine were not a sweet, health-distilling fragrance in a ward filled with sick folk.

The days had now come when the looms of Dixie, hitherto an unknown quantity, were to be busy weaving homespun for its people to wear. But Margaret Drane with her sister and two young friends may claim to be the first of the "Homespun Girls" of Dixie of gentle birth who wore that much derided, homely material. A good-humored merchant of the city, doubtful of their brave, oft-repeated cry to

Page 43

"Live and die for Dixie"

resolved to test them on a point where he was confident their girlish vanity would shake their constancy. It was in the first days of the war when Southern maidens still affected what was dainty and becoming. Cynicus challenged them to put aside their pretty, airy, muslin frocks and walk down the fashionable thoroughfare of Main Street clad in humble homespun. While daring them to do this, he offered to make the material a gift. At once the quick pride of the Confederate girl was touched. She gloried in this opportunity for the sacrifice of personal vanity upon the altar of patriotism. The merchant's offer was accepted so soon as made and the girls marched in a bevy to his store. There they selected the unmistakably genuine article, with their own hands made the dresses in the style of the day - ten widths to the skirt, tight waist and low-corded neck. Wearing their homespun, not as housemaids, but as if it were the ermine of royalty, and trying to keep step in their ungainly brogans; with cornshuck hats of their own braiding, bravely trimmed with red-white-and-red ribbons, shading their blushing faces. the appearance of the quartette on Main Street at once set the patriotic fashion and made them the toast of the hour.

Ah! those early days of a war that had not yet grown cruel and when, to the bounding heart of youth, the drama seemed just enough touched with danger to be wonderfully fascinating and entertaining! In the summer of '61 it was more of a game than a reality. Our girls, from daily visits to the soldiers' target practise, were fired with a spirit of emulation. "Who could tell' - they reasoned - "but what, like the Maid of Saragossa, behind the rampart of cotton bales with which General Pillow has fortified the river front, we, too, may defend our city." True, many of the young maids had learned to handle without fear the pistols coaxed from brothers and friends and, too proud to betray ignorance, after a unique fashion of their own, loaded them. First they carefully rammed in a generous wad of paper, then bullets and all the powder the chambers would hold. But lo! nothing they could do would induce the weapon to go off and the entire contents persisted in rolling out. Again and again the charge was varied, bullets at bottom and paper on top, but of no avail.

Page 44

Possibly the cap was omitted. They could not tell, but cheerily looked to the future to remedy their inexperience and crown them with laurels. By no means discouraged, they turned to the target-practise - shooting with guns and cartridges already prepared and about which there could be no perplexing mixture of contents. Their spirits rose, for it seemed so easy. Margaret led her companions in this as in whatever enlisted the sympathies of her adventurous spirit. Ambitious to excel, she flouted the friendly counsel of her wise but over-mischievous escort, and chose for her first essay a sharp-shooter rifle intended to pick off its victim a mile distant. Averting her eyes, she resolutely pulled the trigger. What fatal ease! There was a terrific bang as if earth and heaven had collided. The rifle was dropped - our brave sharpshooter knew not where, for a space she knew nothing! Dazed by the shock of sound, she fell backward and rolled down hill to be picked up a somewhat bruised and aching young rebel, but irrepressible as ever and burning with the desire to fit herself for the service of Dixie.

If there was one delinquency more than another resolutely frowned upon, and that excited the keenest contempt of a Dixie girl, it was the cowardice of a man that kept him at home in a safe berth and left the fighting to be done by others. The girls looked upon that as a blot which all the power and wealth of the world could not purge away. Those not enrolled and known as "Minute men" - enlisted for the war and ready for the field at a moment's notice - received short shrift at the hands of these young fire-eaters. Margaret bribed a young man, whom she suspected of being unduly slow in entering the ranks, with a promise to mould the bullets he was to fire at the enemy. To do this tardy young Southerner justice it must be said that he was the only stay of his mother and she was both a widow and helpless invalid. But golden hair and eyes of Scottish blue have more than once taken the crook out of the way for a man. It was so in this case. The young man went to an early battle-field taking with him the pledged dozen bullets shining like newly minted dollars. Soon it was his good fortune to return proudly to dangle before Margaret's shining eyes an empty sleeve, and tell her that was her work. And the stouthearted little maiden was glad while she grieved, for the South's true boy had stood General Bragg's grim test of manhood - "To the front to die as a soldier."

Page 45

So the memorable year of 1861 passed away and the shadows were fast deepening over the land. A typical girl of the '60's, our Margaret had sewed, wept and sung for the boys in gray through the golden summer months and early autumn days. At this time there was a Thespian temple in Memphis, newly built, but never opened to the player folk. The grand old "Mothers" of the city took possession of it and through local talent gave concerts for the purpose of equipping several companies with uniforms. Memory recalls one of those tuneful evenings, when all the girls who had melody in their voices gathered upon the stage arrayed in whitest muslin, with reddest roses for jewels, to sing the songs of Rebel-land under the waving Stars and Bars. And the rebel girls sang with a warmth and volume of voice that stirred tender old memories, or touched a patriotic chord whose vibrations set the audience wild with enthusiastic cheering and clapping of hands.

The "Marsellaise," "When this Cruel War is Over," then the sad sweet strains of "Lorena" in clear bird-like notes floated through the hall and a hush, born of its pathos, fell upon all. Who so deservedly proud as Margaret, our Confederate Girl, when one who loved the song told her that she sang it better than a great singer, claiming the fame of an artist! "Lorena" suggested tears and heart-break, so there was a quick transition to lively old favorites - as well known to the audience as the whistlings of their own mocking-bird - such as "Maryland my Maryland," "Hard Times Come No More," "My Mary Ann," with a score of others, but always sliding at the close into the inevitable "Dixie" that was the signal for a shower of bouquets, sonorous hand-claps, pounding of feet, and strong-throated hurrahs.

In the meantime our Confederate Girl retires from the stage to come forth again with the story of her refugee life and subsequent return from Memphis.

Page 46

THE CONFEDERATE GIRL.

PART II.

IT WAS late in 1861 before Commodore Montgomery and Commodore Foote tried conclusions as to superiority of their gunboats under the bluffs of Memphis. Fathers of families, who by reasons of age, etc., were honorably exempt from military service and were at home, thought it prudent to remove to points less exposed to invasion by the common enemy. Margaret Thurman Drane's father - a minister who had figured prominently in the Alexander Campbell debates in Kentucky - decided upon Canton, Mississippi, as a retreat and thitherto our Margaret reluctantly went.

For the active, sunny temperament of our Confederate girl, Canton, a small inland town of Mississippi, proved rather a dull place of residence compared with the constant excitement of the river city, Memphis, in war times. The young girl's madcap energies must needs have a vent and with odd perversity reached their climax in the formation of a Cavalry Company. Among the numerous girls of the neighborhood she soon enlisted sufficient recruits, but, with all its rosebud beauty and grace, in picturesque accoutrements it might have vied with Falstaff's Ragged Regiment. A mixed multitude of mules and broken down army horses bore the joyous, adventurous patriots to the ground where they drilled by Hardee's Tactics. Their bridles were formed of bag ravelings and girths and blankets were made of gunny sacks. There were no privates in this well appointed company - it consisted wholly of officers, the lieutenants alone being seven in number! In her green riding habit Capt. Margaret gaily and fearlessly at the head of troop rode an army horse loaned for the occasion by a young officer at home on furlough. On a certain evening as she rounded a corner on returning from her daily drill, it so chanced that some soldiers were being put through military instruction in the taking of a battery. The drums beat, the trumpets gave forth a blare and the soldiers charged - yells of men and clatter of swords rising above the tumultuous dash and rush of horses.

Page 47

At once, Margaret's brave warrior-steed caught the familiar notes and needs must charge along with its army mates. No check of bit or bridle could change its course. Its mettle was up and the frightened girl, borne up the hill, was carried in the onward rush to the very front of the battery. Once there, having led the onset, the old battle horse halted, its ambition was satisfied; but the cavalrymen made the welkin ring with cheer after cheer for the dauntless courage and gallant ride of blushing Captain Margaret Drane.

Despite her strenuous, open-air life, our girl never lost sight of the practicalities. Confronted by the shoe problem - one that often tried the soul of a Dixie girl to the uttermost - in her own interest she bravely turned cobbler. From an old ministerial coat of her father's she cut out what was known as uppers. Carefully ripping the coat seams apart, she threaded her needle with the silk thus obtained for sewing on the soles, that meanwhile had been soaked in water to make them pliable for stitching. Tiny foldings of the satin lining made strings and lo! her small feet soon twinkled in new comfort and glory as, in pride and gayety of heart, she pirouetted from room to room.

Only six months of refugee life in Mississippi when the illness of a daughter left behind in Memphis called for the presence of one of the family. It was decided that Margaret should go to her. Fortunately, two old men, Messrs. Horton and King, the first well-known to her father, were about to make one of their periodical trips to Memphis. It was hinted that these old men were a brace of smugglers and spies but, as they were known to be on the right side in the war, loyal to the Confederacy and otherwise trustworthy, such small transgressions of the moral code counted for little in those wild days. Delighting in adventure and laughing at the perils of the trip in prospect, Margaret - confided to the care of these old men and with Miss Horton as companion - set forth in a topless buggy to make the distance between Canton and Memphis. It was just after Grierson's raid had desolated the land. The railroads were torn up, bridges burned and the long stretches of country highways were almost a continuous quagmire from the incessant rains. Seven days over these rough army roads, exposed to every whim of weather, brought them to Hernando, Mississippi.

Page 48

In the meantime, Commodore Foote had taken Memphis after a most dramatic naval combat which, from its high bluffs, was witnessed by the citizens. Bragg was in Kentucky and Confederate spies were busy collecting and forwarding him information. The weather was sultry, but, despite the heat the girls had a quilting bee. They made, and wore beneath their hoop-skirts, petticoats, into which were stitched important papers to be delivered to agents in Memphis. Tape loops at the top of these petticoats made easy their quick removal should occasion call for it. Heavy yarn gloves of her own knitting covered Margaret's pretty hands, in the palms of which she concealed dispatches so valuable that she was bidden to contrive their destruction rather than risk discovery.

After leaving Hernando and reaching Nonconnah - the little stream with melodious Indian name five miles out from Memphis - the girls took out their weapons. Bravely equipped with pistols they made the perilous crossing only to fall into the hands of a group of Yankee soldiery drawn up to guard the bank and fire upon all daring enough to come within range of their guns. They were at once halted by a Colonel - an elderly officer who threatened to have them searched at the barracks hard by. Margaret, having her head in the lion's mouth, was bent on saving it from being bitten off. Young in years, yet she was a true daughter of Eve and resolved upon showing a charming candor to this elderly man of war. Extending her gloved hands, palm downward to conceal the bulky dis-patches, and putting out her shapely feet encased in the cloth boots of her own manufacture, with a laughing look in her eyes of Scottish blue, she quickly retorted, "You had better search me when I go out of the city - that is if you can catch me. In our part of the world we have to wear shoes and gloves like these. And sir, you had better be careful for I have a Yankee sister in town."

Her breezy air, perhaps the covert threat implied in her claim to Northern kindred, had the effect intended. The man of war was placated. Bending down, he whispered: "Little girl, I don't believe you have anything contraband.

Page 49